Historically, Prairie Covered One-Third of Minnesota.

The tallgrass prairie plant community is characterized by a complete absence of trees, due to frequent fires. The shrub layer is extremely limited with only sparse patches of low-stature shrubs such as leadplant, prairie rose, wolfberry, and a few other fire-resilient species. Iconic tallgrass species such as big bluestem and Indiangrass dominate, while mid-height prairie grasses like little bluestem, side-oats grama and prairie dropseed also make up a significant portion of the habitat. Forb cover varies and soil moisture plays a major role in determining which species will thrive. Grey-headed coneflower, purple prairie clover, and stiff goldenrod are among the dominant forb species found in the Classroom’s tallgrass prairie.

Historically, tallgrass prairie spanned a third of the state from northwestern Minnesota to the south and southeast of the state. Herds of bison roamed the prairie, grazing on grasses, promoting biodiversity of prairie species, and providing a critical food source for Native Americans. Along with fire, bison played an important role in shaping and regenerating prairie ecosystems. Today, less than one percent of Minnesota’s prairie remains — only about 150,000 acres of the original 18 million. Loss of tallgrass prairie was caused by three major factors: tilling the soil for farming, loss or suppression of fire, and overgrazing by cattle.

Prairies provide food and shelter for a wide variety of wildlife and are home to nearly half of Minnesota’s rare species. Prairies typically need fire every three to ten years to keep woody species at bay and to cycle nutrients back into the soil. Historically, these fires would naturally occur by lightning strike, or be ignited by Native Americans. Saint Paul Parks and Recreation staff manages tallgrass prairies with prescribed burns every three to five years.

Prairie Plants: More than Meets the Eye

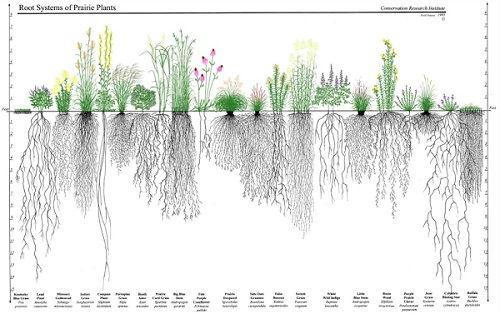

While the aboveground portions of prairie plants provide habitat and food sources for wildlife, what happens belowground is also astounding. Most prairie plants have more biomass below ground than they do above. In fact, approximately two-thirds of plant tissue in prairies exists below ground. These massive root systems provide many benefits to both the plants and the soil they reside in. The intertwining roots are exceptional at holding soil in place and preventing erosion. Each root tendril also serves as a pathway for water and air to penetrate deep into the earth and help recharge ground water.

The root systems of prairie plants are constantly experiencing decay and regrowth. In three to four years of life, a single plant will have a nearly complete turnover of its roots. Decaying roots provide nutrients, contributing to the fertility of prairie soil. As part of the photosynthetic process, prairie plants remove carbon dioxide from the air and store the carbon in their roots.

Photos

- Tallgrass prairie. Photo: Rachel Gardner / CC BY-NC-ND

- Bison. Photo: USDA / CC0

- Root systems. Image: Conservation Research Institute and Heidi Natura