A Workhouse Board Member Observed, Perhaps with No Small Satisfaction, That the Workhouse Tower "Throws Members of the Park Board into Spasms Every Time They Look At It."

The Establishment of the Workhouse

In 1881, when the development of Como Park was delayed by economic conditions and before a park board was in place to protect park interests, Saint Paul granted 40 acres of parkland to the workhouse board for the construction of a new workhouse on land east of the Classroom. Locating a workhouse on unused parkland on the rural outskirts of the city seemed a prudent idea at the time.

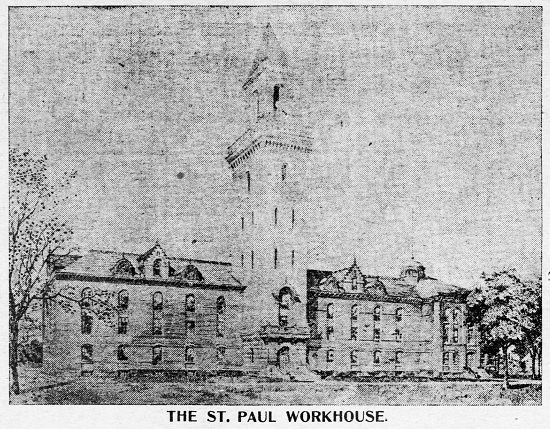

The red brick three-story building opened in 1883 with 30 cells. Its first occupant, David Hoar, a repeat offender described as “a good-natured unfortunate whose appetite has proved his ruin,” was admitted on January 3, sentenced to ten days for drunkenness. Most workhouse inmates were first-time offenders convicted of drunkenness, vagrancy, larceny, or disorderly conduct. Workhouse inmates were put to work for sentences that ranged from five days to a year, with shorter sentences being much more common. The primary purpose of the workhouse was to punish convicts through confinement and work, not to offer rehabilitation. The idea of rehabilitation did not come into fashion until the late 1910s and early 1920s, when reforms such as treatment and halfway shelters were instituted.

The workhouse was a self-sustaining institution. Soon after it opened, inmates helped build an on-site residence for the workhouse superintendent and two additions to the already-too-small workhouse. Twenty acres of woodland were promptly cleared for a farm and garden.

Strife between the Park Board and the Workhouse

In 1887, funds finally became available for park development and a park board was established. Almost immediately the park board decried the placement of the workhouse in the park and called for its removal. Though park board president J. A. Wheelock praised the workhouse in 1895 as “exceptionally well managed” and an important factor in the work of park improvements from 1883-1894, he described workhouse inmates as “not the best kind of labor.”

Despite repeated, vehement cries for the workhouse’s removal, the city couldn’t afford to move it elsewhere. While the workhouse was “temporarily” located in the park, the park board wanted to at least hide its “uncouth and forbidding aspect” behind trees.

In 1898, the park board asserted its authority and took possession of 24.5 acres of workhouse grounds consisting of most of the farm fields. When the workhouse board took the matter to court, the court decided that one city board could not sue another. The park board control of the land was maintained. They began to plant trees.

In 1903, the workhouse added a 150-foot tower to the front of the building. Park superintendent Frederick Nussbaumer declared that the workhouse board, “through an uncontrollable spirit for improvement and electrified by a magic touch of art, built a sentinel … in the shape of a galvanized spire, proclaiming in silent protest, its unpleasant prominence in the surroundings.” The workhouse board replied that the park board had trespassed and spoiled a productive farm, and the tower, while perhaps taller than necessary and architecturally out of proportion, was added for fire safety.

After this, the park board refused to use workhouse labor, calling the benefit of such labor an “old fiction which sought to justify” the workhouse’s “illegal location” in the park. William Pitt Murray, a workhouse board member, defended the workhouse in a 1904 article and observed, perhaps with no small satisfaction, that the tower “throws members of the park board into spasms every time they look at it.”

Nearing the End

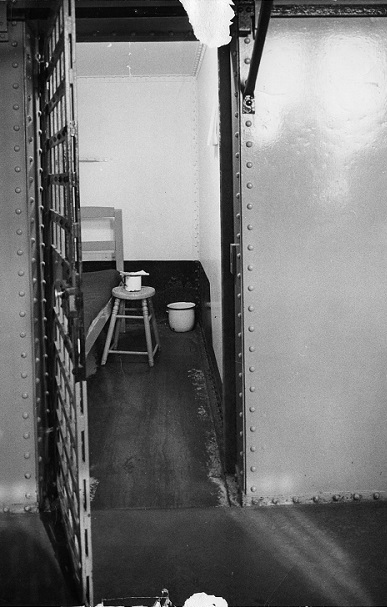

Economic conditions and world events conspired to keep the workhouse in the park and the rhetoric died down. By 1918, the workhouse was already old and obsolete. Its cells had no running water or toilets, it was too small and cost too much to operate, the building wasn’t fireproof (even with the tower), the grounds were too small, and inmates had to walk to work through residential neighborhoods. The building was repeatedly condemned. Each time, makeshift repairs were made to keep it going. Finally in 1960, the “ancient, unloved, and unlovely” old workhouse was torn down after a new facility opened in Maplewood.

Photos

- Workhouse with central tower. Image: St. Paul Globe, Library of Congress

- Workhouse in its later years. Image: Ramsey County Historical Society

- workhouse cell circa 1950. Photo: Minnesota Historical Society